The Forgotten Hostage

It started for the Foreign Press Association the way so many of the hostage takings in the Middle East started – with a small news item on the wires and in the newspapers. This time it was different. This time it was one of us.

British-born New York- based journalist Alec Collett accepted an assignment from the United Nations to go to Beirut in Lebanon in 1985. His mission was to report on the plight of Palestinian refugees for the UN Relief and Works Agency. On March 25 his car was stopped at a road block and Collett was forcibly pulled from his car by terrorists. In messages later, the gunmen claimed to belong to a pro-Libyan group called the Revolutionary Organization of Socialist Muslims.

British-born New York- based journalist Alec Collett accepted an assignment from the United Nations to go to Beirut in Lebanon in 1985. His mission was to report on the plight of Palestinian refugees for the UN Relief and Works Agency. On March 25 his car was stopped at a road block and Collett was forcibly pulled from his car by terrorists. In messages later, the gunmen claimed to belong to a pro-Libyan group called the Revolutionary Organization of Socialist Muslims.

The kidnapping came just nine days after the abduction of Terry Anderson, the Associated Press chief correspondent in the Middle East. Collett is a freelance journalist who worked at the United Nations bureau of the Associated Press, was director of the UN Information Center in Ghana, and wrote for such African papers as the Times of Zambia and the Botswana Guardian.

In May and December of 1985 two videotapes were received of Collett passing on the demands of his captors – that Moslem prisoners in Kuwait be released.

Then, a few days after United States planes bombed Libya in retaliation for a terrorist bombing in Germany, a third videotape was delivered. It showed the macabre scene of a black-hooded man being hung in front of a cheering crowd. A message with the tape claimed the hanged man was Alec Collett, killed in retaliation for the US raid.

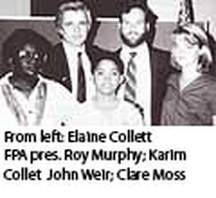

Elaine Collett with family members of American hostages in Beirut at an FPA news conference held to pressure for action on freeing the hostages, June 18, 1985. From left: Elaine Collett; FPA president Roy Murphy; Karim Collett; John Weir, son of Benjamin Weir; and Clare Moss, daughter of Jerry Levin. (Levin had escaped captivity in February, and was made a Life Member of the FPA in December for his constant and continuous work in trying to keep public focus on the plight of the hostages). Photo: M. S. Essakalli

The tape was of poor quality and the man was unidentifiable. The US State Department and the British Foreign Office “could not draw any conclusion” from laboratory studies of the videotape.

If he is still alive, Alec Collett is 71 years old. He has two adult children from his first marriage. His American wife, Elaine, and son, Karim, 11 years old when his father disappeared, live in New York.

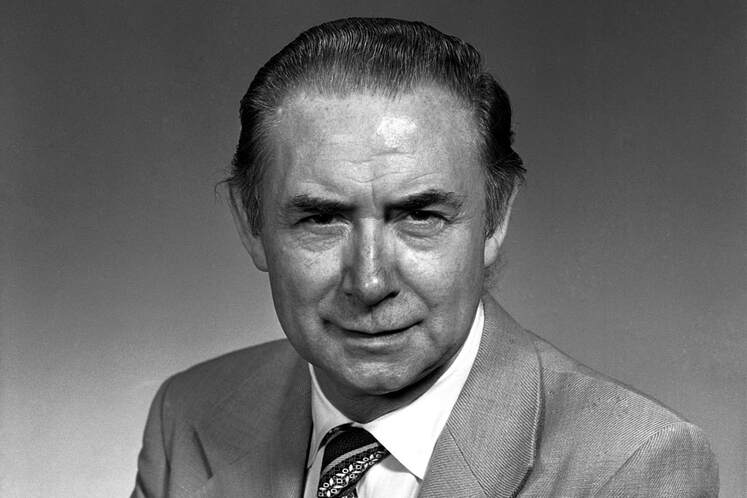

Then-president of the FPA, Roy Murphy, said Collett was a particularly outrageous target for the terrorists because of his work for the homeless Palestinians, as well as his strong connection with third-world publications. The FPA elected Collett a Life M ember – his photo appears on page 14. The UN Correspondents Association voted him as honorary president in December 1986 and PEN American Center made him an honorary member earlier that year.

Collett shows how easy it is to be forgotten. He is not considered to be part of the group of American hostages because he is a British citizen, although his wife and child are American and he has lived in the US for many years. Because his family lives h ere and is American, little pressure can be brought on the British Government for action. And because his whereabouts and fate are unknown, he is more easily ignored by everyone.

Although his wife, Elaine, has borne the ordeal with remarkable courage and dignity, the pain continues on a daily basis. In a rare expression of personal protest, she wrote an article published in Newsday in 1991 shortly after the Gulf War was over. Referring to the families who lost one of their members in the war, she said: “Those families know. At least they know. They can grieve, and mourn, and bury their dead. Eventually they can go on with their lives. . . . After six weeks of war, they have answers. After six years of limbo, our grief is still fresh.”

It is now eight years of limbo for Elaine, her family and all of Collett’s friends and colleagues.

As Eileen Lottman and Hannah Pakula of PEN said in the New York Times, “Until Mr Collett is returned or reasonable proof of his death is given, we cannot accept the comforting fiction that all the surviving Western hostages are now free.

Roy Murphy

In May and December of 1985 two videotapes were received of Collett passing on the demands of his captors – that Moslem prisoners in Kuwait be released.

Then, a few days after United States planes bombed Libya in retaliation for a terrorist bombing in Germany, a third videotape was delivered. It showed the macabre scene of a black-hooded man being hung in front of a cheering crowd. A message with the tape claimed the hanged man was Alec Collett, killed in retaliation for the US raid.

Elaine Collett with family members of American hostages in Beirut at an FPA news conference held to pressure for action on freeing the hostages, June 18, 1985. From left: Elaine Collett; FPA president Roy Murphy; Karim Collett; John Weir, son of Benjamin Weir; and Clare Moss, daughter of Jerry Levin. (Levin had escaped captivity in February, and was made a Life Member of the FPA in December for his constant and continuous work in trying to keep public focus on the plight of the hostages). Photo: M. S. Essakalli

The tape was of poor quality and the man was unidentifiable. The US State Department and the British Foreign Office “could not draw any conclusion” from laboratory studies of the videotape.

If he is still alive, Alec Collett is 71 years old. He has two adult children from his first marriage. His American wife, Elaine, and son, Karim, 11 years old when his father disappeared, live in New York.

Then-president of the FPA, Roy Murphy, said Collett was a particularly outrageous target for the terrorists because of his work for the homeless Palestinians, as well as his strong connection with third-world publications. The FPA elected Collett a Life M ember – his photo appears on page 14. The UN Correspondents Association voted him as honorary president in December 1986 and PEN American Center made him an honorary member earlier that year.

Collett shows how easy it is to be forgotten. He is not considered to be part of the group of American hostages because he is a British citizen, although his wife and child are American and he has lived in the US for many years. Because his family lives h ere and is American, little pressure can be brought on the British Government for action. And because his whereabouts and fate are unknown, he is more easily ignored by everyone.

Although his wife, Elaine, has borne the ordeal with remarkable courage and dignity, the pain continues on a daily basis. In a rare expression of personal protest, she wrote an article published in Newsday in 1991 shortly after the Gulf War was over. Referring to the families who lost one of their members in the war, she said: “Those families know. At least they know. They can grieve, and mourn, and bury their dead. Eventually they can go on with their lives. . . . After six weeks of war, they have answers. After six years of limbo, our grief is still fresh.”

It is now eight years of limbo for Elaine, her family and all of Collett’s friends and colleagues.

As Eileen Lottman and Hannah Pakula of PEN said in the New York Times, “Until Mr Collett is returned or reasonable proof of his death is given, we cannot accept the comforting fiction that all the surviving Western hostages are now free.

Roy Murphy